The History of Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation

Nisachawayasihk Cree Nation History Book

Respecting Our Past…Creating A Bright Future

The following information has been taken from the Nisachawayasihk Cree Nation – History: Respecting Our Past…Creating A Bright Future book. To read or download a PDF version of the book click the button below. Printed soft cover versions of the book are available through the NCN Government Office.

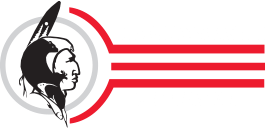

Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation History Timeline

Our History At-A-Glance

As Citizens of Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation, we are proud of our deep-rooted history dating back thousands of years. Traditional story telling (achimowenu) and legends (achuthokewenu) once flourished through our beautiful Nehetho language. Our history, land, and laws are still embodied in our language and culture. We must share the truth and the reality of who we are. The timeline summary below illustrates many of the key accomplishments, hardships and even Colonial atrocities we’ve had to overcome. These events have shaped our lives, connected us with our memories of our ancestors and now direct us on our pathway to a promising future.

Where Three Rivers Meet

The Intersection of Past and Present

We are the Nisichawayasi Nehethowuk, the people whose ancestors lived near where the three rivers meet and who speak Nehetho, the language of the four winds.

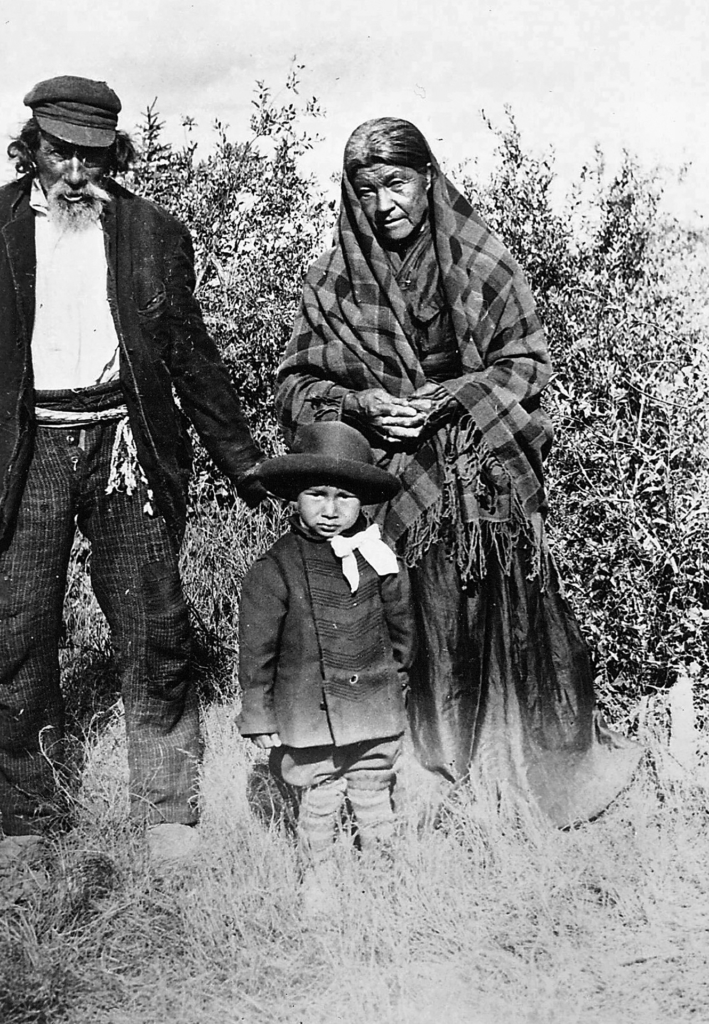

Nisichawayasi people have been connected to the land and waters where the Burntwood, Footprint and Rat Rivers converge for over ten thousand years. After the Adhesion to Treaty 5 was signed in 1908, Indian Reserve 170 was created and became the formal homeland of Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation. For millennia, we have relied on the waterways for transportation, and what is now called Nelson House, was a strategic location within our traditional territory. This likely influenced the Hudson’s Bay Company’s choice of the site for a trading post around 1800.

Our ancestors were nomadic people who lived far beyond the boundaries of the current reserve. They had an intimate knowledge of our traditional territory which extends over a 23,000-square-kilometre region which extends beyond the area now referred to as NCN’s resource management area which follows the boundaries of the provincially established trapline zones. Our ancestors also traded with other Nations beyond our traditional territory.

These beautiful, rich traditional lands in Canada’s pre-Cambrian Shield and northern boreal forest encompass tracts of black and white spruce interspersed with many rivers, streams and lakes. Kehchi Manitou (the Great Spirit), through Kehchi Othasowewin (the Great Law) granted us, as the guardians of N’tuskenan (our sacred land) the responsibility to care for, and the right to use and benefit from its resources.

The people were remarkably resilient and thrived in an often-harsh environment and climate characterized by short summers with long hours of daylight and long, cold winters with little daylight. They were able to overcome hardships and adversity for generations due to their close kinship and strong sense of community. This spirit of resilience continues and characterizes our people and our values today. Our customary laws are based on the seven sacred teachings of our ancestors as represented by the animals to remind us of our connection to Mother Earth.

To this day, many Nisichawayasi believe our lives are guided by a belief that it is important to keep a balance between the four realms of “our being” (spiritual, physical, intellectual and emotional).

Legends of the Land and Ancient Past

The Importance of Stories and Culture

Our people have a deep and enduring connection to the land and its sacred, historic, burial sites, and culturally significant places and place names. NCN’s modern culture is rooted in the ancient past and the traditional 13 teachings of the Great Law (Kihche’othasowewin) and customary and natural laws that continues to be respected.

We, and other Aboriginal people, recognize the land and waters and all they provide as vital to their existence. “Mother Earth” is revered, respected and acknowledged during ceremonial events.

The Nisichawayasi Nehethowuk have many sites of cultural significance near Otohowenehk and Wapanukahk (Three Point Lake) that give meaning to our Nehetho (Cree) way of life.

At the time of treaty our natural laws were shared with newcomers. These laws formed the basis for the treaty and recognized our Tipethemisowin (full sovereignty as a nation).

Our reverence for the land is enhanced by rich legends, some of which are shared by other indigenous peoples across the Northern

boreal forest.

The legends, stories and our historical experience have contributed to a unique cultural perspective. Our Elders and storykeepers connect us to the ancient teachings and traditions.

Prominent in our legends is Wesahkechahk, a kind and loving spirit and legendary Nehetho cultural hero and teacher. The stories of his journeys have played a significant role in the continuity of our Nehetho identity for countless generations. His travels range across vast expanses of the boreal shield, and he plays a significant role in our story-telling tradition.

Footprint Lake is named for the footprints left there by our spiritual hero and our brother Wesahkechahk. The footprints are rock features prominent in Nehetho legends and known throughout northern Manitoba. A reproduction of them can be seen at the Manitoba Museum in the Boreal Forest Gallery. The original Footprints, removed without our consent have recently been returned to a site near their original location.

Natural features associated with Wesahkechak are found across the boreal shield country

- His chair and footprints are in rock formations at Footprint Lake, to the northwest of Nelson House.

- The Vision Quest site in Prayer River and the island that rotates near Wapapiskasihk on the Rat River.

- His spoon is in a rock formation on the upper Severn River east of Lake Winnipeg.

- A row of hills at Beaver Hill Lake near Island Lake is where he danced all night with his eyes shut.

- Island Lake was made by Wesahkechahk when he broke a beaver dam.

- Soskwuchewewin is a sacred slide where spirits land in the mountains in Alberta near Calgary.

Besides, Wesahkechak, NCN‘s ancestral homeland is also associated with Mimikwisihwahk, the legendary little rock people. A little south of the chair is a stone boat feature attributed to the Mimikwisihwahk.

It is estimated there were 39 sites identified and there are many more, but the funding ran dry. NCN is honoured to have three of these special sites within its ancestral homeland.

After The Ice Mountains

Our Ancestors Explored and Inhabited the Land after The Glacier’s Retreat

Many historians and NCN Citizens often refer to our Nehetho presence in North America going back to “when time started” but according to Mechemach’ Ohchi our presence on the land might be closely described as a time without a date.

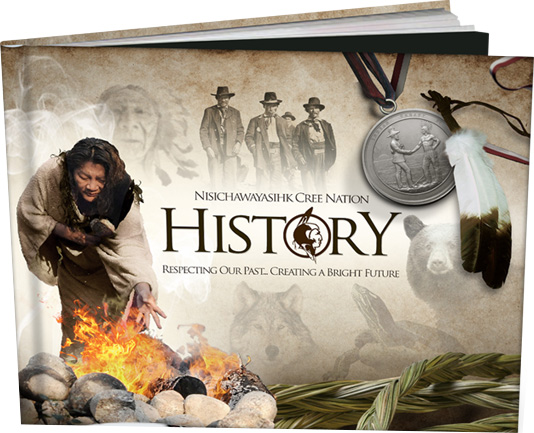

Archaeologically, our ancestors’ presence in our existing territory can be traced back nearly 10,000 years after mile-thick ice sheets retreated north and Glacial Lake Agassiz had drained to expose the land. Climatic change likely prompted the move with a global shift to warmer, drier conditions.

Archaeological records suggest that around 7,500 years ago, shortly after the ice mountains melted and glacial Lake Agassiz began to recede, ancient people started to explore the new surroundings as vegetation and animals began to inhabit the landscape in the region near Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation (Nelson House).

Oral stories from the south tell of a time when “ice-runners” kept an eye on advancing and receding glacial ice but any evidence of them has been lost. The Nehetho call this time Mawatch’ Kuyas.

Early evidence of human movement during the ice age is found to the west in the Central Plains following herds of large game animals that foraged north as the vegetation improved. Our ancestors may have reached the northern limits of their traditional lands in what is now Nunavut. They slowly moved south and southeast from Nunavut into northern Manitoba, possibly traveling over 300 kilometres along raised glacial eskers as natural highways southwest to Lynne Lake and into N’sihcawahsihk – Three Point Lake.

Cultural groups at the time adjusted their big-game hunting strategies to include smaller game animals, birds and fish. The oral practice of passing down knowledge and experiences of the past thousands of years from one generation to the next through narrative, legend and oral history likely matured during this time.

Touching the Past

Clay Pots, Stone Tools and Human Remains Connect Us Directly with our Ancestors

Our nomadic Ancestors, living in the boreal forest before European contact, used the clear lakes, rivers and streams as their equivalent to our modern highways. They also provided the life-giving resources of the diverse plants, animals, birds and fish in and near the water. As well, the waterways provided access to adjacent well-drained uplands and low wetlands that supported a wide variety of berries, medicines and wildlife.

Most ancient camp sites have been found on lake shores, and many of the sites that were prime locations over a thousand years ago are still used today. The same groups or families often used several sites over the year, each one associated with special activities or significance such as fishing, hunting, dancing circles, ceremonial sites, named places and sites for gathering medicines.

Our ancestors left things behind at these camps like clay pots, stone tools and arrowheads that survived over the centuries. These have become precious and tangible links to our ancestors and our history. The design and materials used in some of these items indicate they were not made locally but obtained through trade with other Aboriginal groups who lived thousands of kilometres away – as far south as Mexico.

After Europeans arrived on the continent, items like glass and iron obtained through trade could also be found. It is evident from the belongings our ancestors left behind that they had contact and traded with other Aboriginal groups who had already encountered Europeans long before they settled North America.

More than 500 archaeological sites spanning 10,000 years of occupation have been identified in the NCN area alone.

Europeans and the Fur Trade

We Were the Essential Player in Canada’s First Economy

Nisichawayasi Nehethowuk continued in harmony and balance with their environment for many hundreds of years. But in the late 1600s and early 1700s foreign trade goods began to make their way into the interior as First Nations peoples in today’s Manitoba became involved in the fur trade. It is believed it was because of the Nehetho generosity the Europeans learned to survive the wild climates and live off the land. Indigenous people of the area shared safe travel routes and many teachings about the land and waterways.

At first, the Nisichawayasi Nehethowuk travelled to either Churchill or York Factory on Hudson Bay where the British had built two large forts.

But, by the late 1700s the Northwest Company and Hudson’s Bay Company built a number of trading posts and forts at strategic locations near First Nations’ settlements in order to trade with the local people. The Hudson’s Bay Company established a post at Nelson House where our ancestors traded beaver, fox and other furs in exchange for goods such as tea, sugar, flour, woven cloth, tools, other utensils and liquor. At this time so-called “country marriages” took place between the HBC indentured servants and Nehetho women. Many of their children continued to work for the HBC, while others returned to their ancient roots.

With the establishment of the fur trade, our ancestors, although still nomadic, had regular contact with European fur traders and voyageurs and they would come to the Nelson House post to trade their furs for European goods. By the time the Treaty was secured over a century later, NCN Citizens had become less nomadic and more settled in and around Nelson House.

As contact increased, the integrity of our culture was also affected through exposure to European culture. Written records were added to our oral traditions that, until then, were the only way our history, culture and stories were shared over generations.

During this period and up to the late 1800s, our people played a critical role in the economy of the country.

We were an indispensable part of the fur trade, providing traders with the necessary intimate knowledge of resources and the land along with ways to survive in an unforgiving region. The fur trade in fact could be considered the first commercial resource-extraction activity in Canada and our NCN ancestors were engaged in this activity from the 1600s until the mid-1800s when changing fashion trends in Europe led to a collapse of the industry and economic distress for Aboriginal trappers.

With the influx of more European immigrants into First Nation traditional territories and with the subsequent formation of Canada as a nation, Canada’s Aboriginal people including our ancestors lost their independence and were relegated to often very marginal land on reserves.

Cases of infected blankets given to Indigenous people caused many deaths and we began to see the negative influences brought to our people.

This increase of newcomers and the pursuit of assimilation policies by them as well as other subsequent events that followed began an era of “cultural genocide” for NCN and other First Nations. Our ceremonies like the Sun Dance and Vision Quest became unlawful and use of our language and other cultural practices were discouraged.

Life on the Reserve Begins

NCN’s Adhesion to Treaty 5 Recognized Us As A Distinct People

The 1215 Magna Carta, Royal Proclamation of 1763 and Adhesion to Treaty 5 were significant turning points in our long history. These agreements shaped the Canadian Constitution and governance of the land we called home.

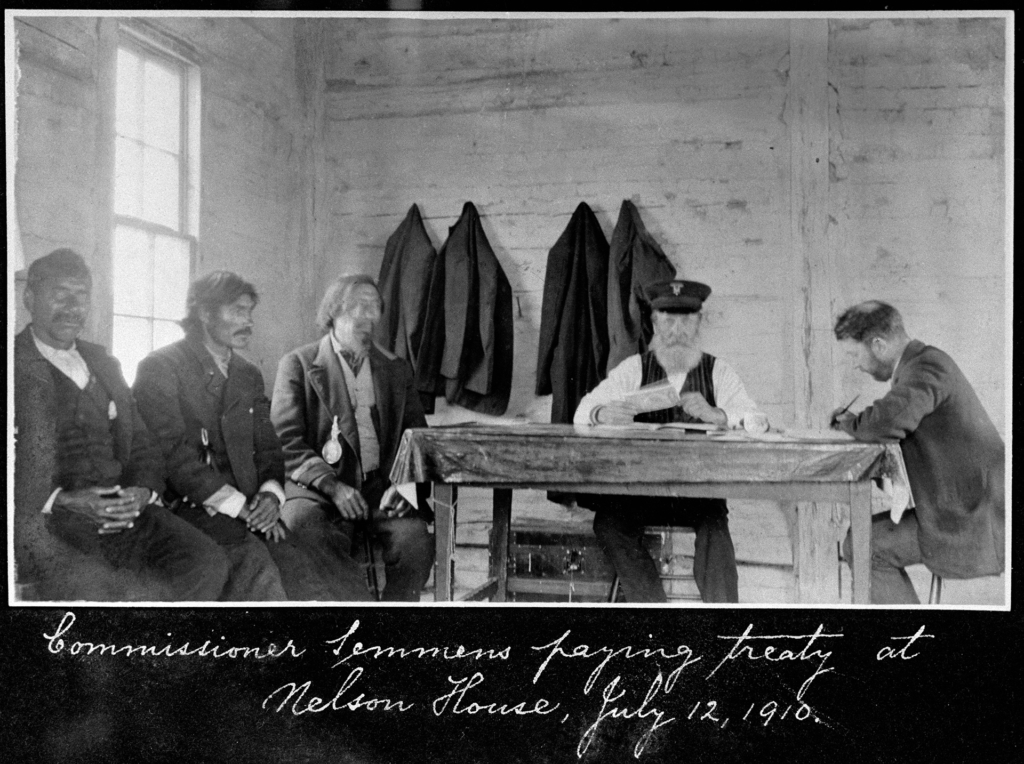

Treaty 5 was first created in September 1875 between the Crown and First Nations in Berens River and Norway House.

The Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation signed an adhesion to that treaty 33 years later on July 30, 1908. Tataskweyak Cree Nation of Split Lake signed a few days later. We were never fully compensated for those years as part of the original Treaty even after we signed the adhesion.

Our chief at the time, Pierre Moose, and two councillors, Murdoch Hart and James Spence, represented Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation at

the adhesion ceremony in Nelson House.

The 1908 Adhesion to Treaty 5 was negotiated because we recognized the need to make a Treaty with the government of Canada to safeguard our way of life in our ancestral homeland. It is important to note leaders did not ask for a reserve. It was said to be “forced” on them and because of inadequate translation and a lack of understanding when oral promises were converted into the written English language – they proceeded on trust and faith.

At the time of the treaty-making, the Crown claimed the lands and all the natural resources were “owned” and controlled by the government of Canada. However, NCN’s view was that it never relinquished any land or allodial rights (ownership of land independent of a government authority) during the treaty making. The Crown just assumed the land as the de facto authority. NCN did not release any body of water within its ancestral homeland since it is believed that no person can claim ownership to water, air, and the other orders of creation. Instead we are all related to the other three orders of creation and we treat them as living entities.

Regardless of the misunderstandings about our lands and waters, at its most fundamental level, the treaty was an acknowledgement of the Nisichawayasi Nehethowuk as a distinct people who were to be respected. The Treaty also defined us as sovereign people with our own history, land, people, language and future. It recognized we were here long before the Europeans and inhabited and relied on the lands of Northern Manitoba for our sustenance. Whereas Europeans viewed land and territory as a tangible asset to be owned, we and other Aboriginal peoples had always viewed land as a gift from the Creator to provide for our needs. We did not own it, but only used it and we understood we had a sacred responsibility to care for it.

We were pleased to share the bounty with the Europeans and a treaty seemed like a reasonable accommodation. Through the treaty, we relinquished any claims to the vast areas of Northern Manitoba in exchange for a defined reserve and other benefits – a concept more in line with European ideas of land ownership and contracts than anything we were familiar with.

The Treaty appeared to be working fairly well initially until the federally appointed Indian Agents began to impose the rules of the Indian Act (1876) on us and the Natural Resources Transfer Agreement of 1930 was passed. At this time the Federal Government turned over control of Crown lands and natural resources to the Provincial government. This amendment to the Canadian Constitution, 1867 was passed without consultation or the consent of Manitoba’s Aboriginal peoples and is viewed as a violation of the treaty by our people.

The powers this new legislation gave the Province and their implications for northern First Nations began to surface with the authority of Provincial Game Laws and the imposition of the Registered Trap Line System upon First Nation trappers with the active assistance of the Indian Affairs Branch. Most disturbing of all was the removal of our treaty rights to hunt, trap and fish commercially which had always been a fundamental part of who we were as a people.

As we moved into the modern era, the Treaty helped to define us as a people, for better or worse.

Over the past century we have not only survived but also persevered. Some promises in the treaty however were never fulfilled or there was discriminatory treatment between different First Nations which resulted in lesser benefits for giving up the same rights. These issues are still unresolved in many cases today and so we are trying to negotiate a fair and just resolution to these historical claims. But as we are a patient, resourceful people we are still acquiring the resources and putting in place the agreements and governance systems we need to create a bright future for our children. We are including our language and our customary laws in these agreements.

South Indian Lake Independence

For nearly 100 years, the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation united in its aim to have South Indian Lake recognized as a separate First Nation from NCN, to be known as O-Pipon-Na-Piwi Cree Nation (OPCN) – setting apart the community as a reserve.

On December 22, 2005 nearly 1,000 Citizens separated from NCN to form OPCN. The First Nation’s reserve lands include over 28,000 acres and it has its own government.

The Advantages and Challenges of the Twentieth Century

Faster Isn’t Always Better

In the early 1900s NCN’s ancestors saw the outside world encroaching, including the first rail line to the north.

NCN’s strategic network of waterways still served Citizens well, but access to the outside world was becoming much faster and easier with the invention of air travel in 1903. After World War I, planes and their often military-trained pilots quickly began opening up Canada’s north.

The first aircraft into Nelson house transported NCN resident Lionel Lobster from Otohownehk to receive life-saving medical attention after being attacked by a bear.

A fur buyer chartered Canada’s first commercial flight into the north between Winnipeg and The Pas in October 1920. Regular flights first came into Nelson House in the 1920s, mainly to bring supplies and mail. With pontoons and skis, planes could land and take off on water, snow or ice almost anywhere using the same waterways our people travelled by canoe for millennia. Bush planes like the de Havilland Beaver had the ability to cruise at 230 kilometres per hour and although fast, flying was expensive for NCN Citizens and restricted access. But it allowed people from afar much easier access to the community. An airstrip was built in the area at R.C. Point which is now residential housing. It was in place until after road access was built.

It was only in 1974 that road access came to Nelson House and made easy, inexpensive and fast travel to and from the community accessible to all. It gave more NCN Citizens the ability to see the outside world and marked an abrupt transition from reliance on the waterways for boat and air travel to land-based travel for moving people, supplies and goods.

Way of life changed drastically for NCN people. Access to drugs and alcohol created social and health issues. Family structure began to break down and traditional roles of men and women changed. The residential school system started to take children from their families, homes and communities – further adding to problems that would affect generations. Effects that had never been seen in the thousands of years prior to treaties and were never agreed to as part of the treaty-making agreement.

The Tragedy of the Residential School System

A Challenge and a Measure of Our Resilience

As NCN Citizens have increasingly engaged in the outside world over the past century, several significant events have profoundly affected our Citizens or encroached on Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation’s ancestral homeland.

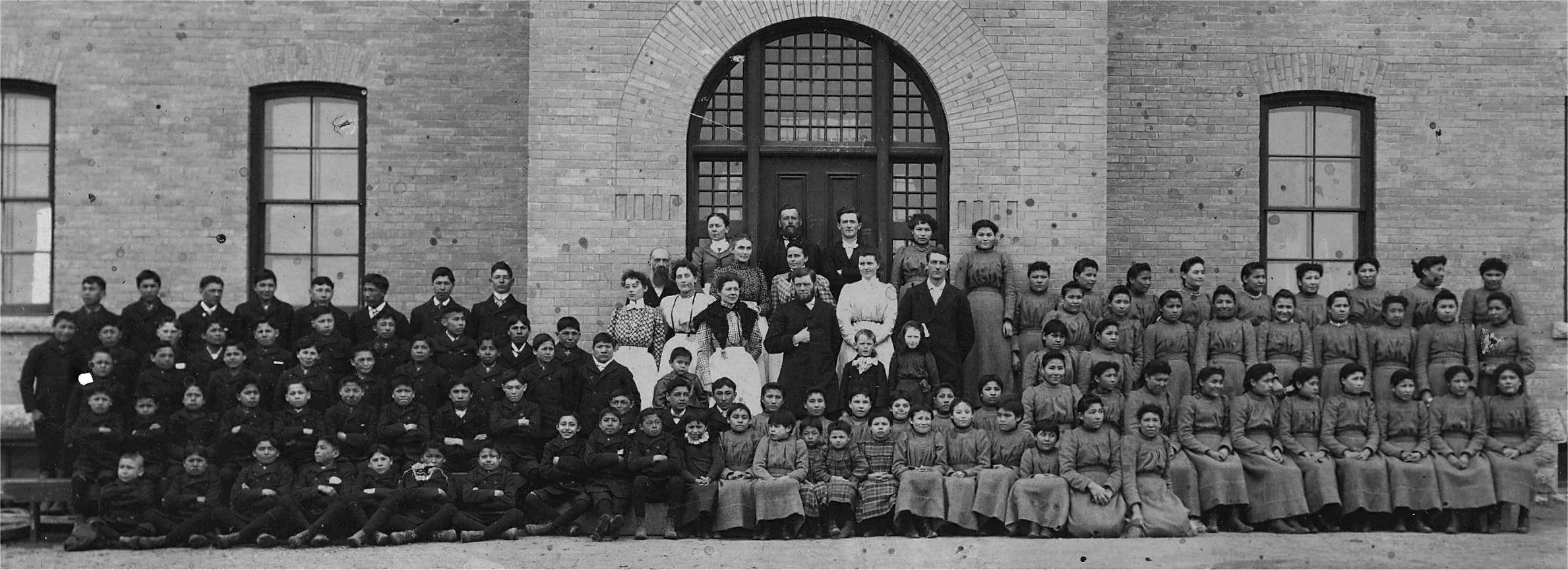

Tragedy surrounded the school system; on-reserve day school students, taught by the churches, reported physical and sexual abuse; administrators had more control than the leaders in the communities and a new religion was brought to the Nehetho people.

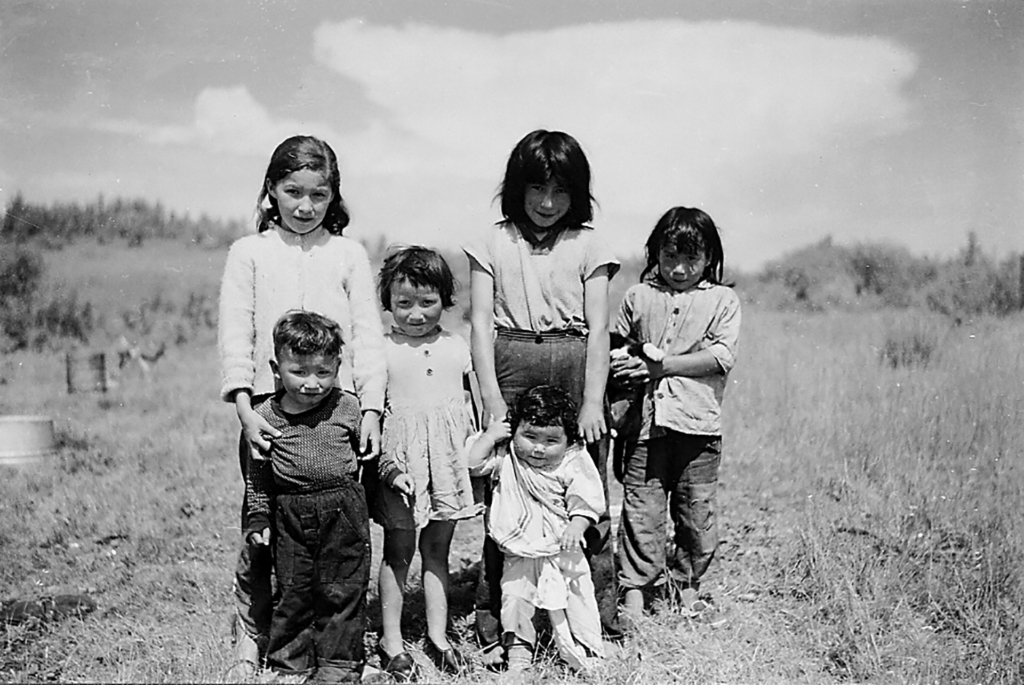

NCN was caught in Canada’s residential school system tragedy. Beginning in 1920 the Indian Act made attending government-sponsored, church-run residential schools mandatory.

Indian residential schools in one form or another date back to the 1880s but were finally closed down in the 1980s. More than 150,000 children attended residential schools across Canada over that period.

During this era of colonialism, almost all NCN children were forced to assimilate into a foreign way of life. They had to leave their homes, families and communities between 1920 and 1974 with many sent away to schools in Winnipeg, Brandon and elsewhere. The goal was to acculturate Aboriginal children into the European-dominated Canadian society by removing them from the cultural influences of their home communities. They were often forbidden to speak their native languages or observe their traditional beliefs. Families were split up and children from the same family were sent to different schools or were not allowed to share rooms with their siblings.

NCN knowledge keepers’ recall when the first group of six children were sent to residential schools in Red Deer, Alberta only three returned. The others, who attempted to flee the schools, were said to be buried in unmarked graves.

The schools were underfunded, often poorly managed and badly built. Because of underfunding, students were rarely fed well and lived in overcrowded housing. Disease and death were common early in the past century and horrible health conditions were ignored. Children were called dirty or savages and their self-esteem suffered.

Mandatory attendance ended in 1969 but physical, emotional and sexual abuse was common and endured until the schools closed in 1986. By then, authorities admitted failure and some First Nations including NCN sought local control of their children’s education. Unfortunately, decades of residential schools left its negative mark on our community as it did on others.

In 1981, NCN established the Nelson House Education Authority that took over responsibility for education from Indian and Northern Affairs Canada and we now provide all on-reserve elementary and high-school education and administer post-secondary education funding. However, the curriculum is established by the provincial government and we are required to follow it. It does not yet include traditional cultural teachings or fluent Cree language courses which we are trying to rectify on our own.

For many NCN Citizens, the trauma of residential school life endured into adulthood, creating social problems, out-of-balance lives and substance abuse to escape the memories.

Children deprived of living with their own parents did not learn important parenting skills, kinship and other social connections themselves, which led to intergenerational problems in raising their own families.

In 2000, the Nelson House Medicine Lodge opened the Pisimweyapiy Counselling Centre (PCC) to work with NCN Citizens to help heal the devastating inter-generational impacts of the Indian Residential School system. Almost 440 NCN Citizens, many the children of residential school survivors, participated between 2000 and 2010 when the program ended.

After court action, the federal government enacted the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement in May 2006, which provided financial restitution to residential school survivors for abuse and trauma. NCN Citizens who were residential school survivors were eligible for compensation. The agreement also established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada with a mandate to provide a forum for survivors to tell their stories of abuse. Many NCN Citizens have participated.

In 2015 the TRC concluded, after six years of research that the treatment of Aboriginal peoples in residential schools amounted to “cultural genocide.” The Commission recommended that “culturally appropriate” child welfare systems be put in place to keep families together where possible. NCN developed a unique proposal to improve child/parent care by removing the parent from the home, and providing new caregivers – rather than displace the children. The Canadian Government also began to officially recognize the tragedies of this era although progress to mitigate the negative impacts has remained slow.

The locally run NCN Family and Community Wellness Centre has been leading the way in innovative approaches to healing the generational impact and tragedies of the residential schools with its Intervention and Removal of Parent Program. The program has been running since 2001 to reduce the disruption and trauma to children and improve Mithwayawin (wellness).

Assimilation of First Nations

The Catholic Church’s view of First Nations people in the 15th century as stated by the Papal Bulls of Discovery, granted explorers complete impunity in their dealings with First Nations. The decrees granted Catholic explorers “full and free power, authority and jurisdiction of every kind” to “conquer the New World and the ‘heathen’ Aboriginals that call it home.” It was stated it was their duty “to lead the peoples in those countries to embrace the Christian religion” and granted them the right to enslave and kill any Aboriginal people who resisted. Impacts of these words are believed by knowledge keepers to have impacted the way Canada’s residential schools were operated. First Nations children were taught that they were “lesser people, without a soul” and “this is why they can not own lands.” All of these teachings had a negative impact on the self-esteem of successive generations of children and their parents.

Northern Resource Development

A Marginal Role and Damage Done Leads to a New Resolve to be a Participant

From before the signing of the Adhesion to Treaty No. 5 to the present, a major concern has been the impact of destructive change from the outside on our land, lives, and livelihood. Many changes have occurred to the Nehetho way of life since the appearance of non-Aboriginals in our ancestral homeland. First was the fur trade, and then within the last century, the building of the railway through our ancestral homeland. Since then, mining, forestry, and commercial fishing developed.

Modern resource development has been occurring in northern Manitoba since the early 1900s with the discovery of rich copper deposits in Flin Flon in 1915 along the Saskatchewan Border.

Much closer to Nelson House, about 80 kilometres to the east within NCN’s traditional territories, one of the world’s richest nickel deposits was discovered in 1956 near present-day Thompson – a city created to service the mine. Thompson and the INCO mine were developed without the Manitoba government, Manitoba Hydro or INCO providing any consultation with or compensation to NCN. The project went ahead despite unclear interpretation of the use of the land in the agreements.

Hydro Development and the Devastation of the Churchill River Diversion

To service the INCO nickel mine and Town of Thompson, Manitoba Hydro constructed the 211 Megawatt Kelsey Generating Station on the Nelson River. Construction began in 1957 and the station went into service June 23, 1960. It was followed by four additional generating stations between 1970 and 1990 now operating on the Nelson River to serve the growing appetite for electricity in southern Manitoba, and the northern United States.

The generating stations themselves did not directly affect NCN. It was the Crown corporation’s plans to optimize water volumes and flows for power production on the Nelson River by supplementing and regulating water flows through the Churchill River Diversion and Lake Winnipeg Regulation that had the major impact.

The Churchill River Diversion, approved in 1970 by Canada and Manitoba and completed in 1976, redirected the Churchill River into the Rat and Burntwood Rivers to Split Lake and then to the lower Nelson River.

This resulted in substantial flooding near Nelson House, South Indian Lake, then a part of NCN, and within our traditional territory with water levels increasing in some places by 30 feet. This too was done without any meaningful consultation with our First Nation.

The flooding produced substantial shoreline erosion, floating debris, and changes to water quality. It disrupted traditional waterway travel and resource-harvesting practices in the area and people could no longer fish, trap hunt and gather as they had resulting in substantial hardships and destruction of our way of life.

Northern Flood Agreement – a Flawed Process

NCN was not the only First Nation affected by Manitoba Hydro’s developments. Others along the Nelson River were also affected by generating station development. Finally in 1976, five northern First Nations, including NCN, formed the Northern Flood Committee (NFC) and opposed the hydro-electric projects. By December 1977 the Northern Flood Agreement (NFA) was negotiated and ratified.

At the outset of negotiations, it soon became apparent that as far as Manitoba and Manitoba Hydro were concerned, they were not prepared to recognize we had any rights to the land and resources outside the reserve boundaries, apart from our treaty rights for hunting and fishing.

The Committee was initially able to get the two governments and Manitoba Hydro to come to the table to begin negotiations about the impacts of the hydro-electric projects on their land, lives and livelihood. The NFC had no financial resources but was able to get the support of their citizens and eventually limited financial support from Canada in the form of bank-loan guarantees. The negotiations resulted in the signing of the NFA in 1977.

The NFA contained many promises for action, but it’s ambiguous wording resulted in each party having different interpretations about specific implementation plans. The NFA provisions for arbitration, which allowed any dispute among the parties to be arbitrated, eventually became the only way to try to force the implementation of the NFA. But it also allowed the parties to stall implementation by letting every dispute or claim go to the arbitrator. Arbitration became a long, tedious and difficult process that did not serve the five First Nations well.

The NFA, despite its imperfections, was a legally binding agreement intended to ensure that any further hydro-related project development on the Lower Nelson River would involve the signatories to the NFA.

Northern Flood Comprehensive Implementation Agreement Brings New Hope and Resolve to Manage our Destiny

Parties to the Northern Flood Agreement recognized a solution was needed to the ongoing delays and failure to implement the NFA. Various negotiations took place but eventually around 1990 the “proposed basis for settlement” among the five First Nations fell apart and each went their separate ways. NCN began negotiations on its own in 1992. We negotiated a new agreement that was ratified in late 1995 and signed in March 1996. The 1996 NFA Implementation Agreement clearly defined compensation for the Churchill River Diversion’s impact.

It provided NCN with a substantial monetary settlement of over $56 million plus annual interest on the hydro bonds. The bulk of the settlement proceeds were placed in the Nisichawayasihk Trust that continues to generate annual revenue for community programs.

This accomplishment gave us a sense we could move beyond the Churchill River Diversion to create some positive things to help ensure our kids could focus on the future and not the past.

A key provision of the Implementation Agreement was Article 8, which spelled out Manitoba Hydro’s obligation to consult on any future hydroelectric-development projects in our traditional lands. It is important to note we had to walk away from the negotiating table for 9 months in order to ensure no further hydro development could take place in our traditional territory without our involvement and the conclusion of compensation arrangements BEFORE not AFTER the project was built.

This was a critical factor leading to joint development of the Wuskwatim Generation Project. It also helped reinforce the importance of asserting our sovereignty in the pursuit of economic development which led us to change our name from the Nelson House First Nation (which was based on the Indian Affairs name, Nelson House Band of Indians we had been given historically), to the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation. Concurrently, we adopted our Vision Statement which is “to exercise sovereignty that sustains a prosperous socio-economic future for the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation.”

Living off the Land in a New Way

The Wuskwatim Generating Station Partnership

Shortly after the 1996 NFA Implementation Agreement was signed, Manitoba Hydro came to us with a new proposal to develop the Wuskwatim generating station at Taskinigup Falls on the Burntwood River.

We were proactive from the start and told Manitoba Hydro that we would not agree to a 350 megawatt plant that would have resulted in significant new flooding. NCN indicated at the outset we would only consider a 200 megawatt project which would cause minimal flooding, if there were significant benefits for our community. Even raising the possibility of new hydro development within our territory was fraught with challenges as our people did not trust Manitoba Hydro or the other levels of government.

Therefore, both Manitoba Hydro and NCN knew if this project was to proceed it would have to be a lot different than the Churchill River Diversion project. And, it was. Rather than Hydro just developing the project with little participation from NCN, we developed an equity partnership so we could share directly in the benefits.

The PDA provides the basis for our unique partnership with Manitoba Hydro. It references our customary laws and for the first time the environmental assessment process treated our Ethinesewin equally and meaningfully with western science in the development of the project. The agreement is historic and groundbreaking, representing the first time in Canada that a major public utility entered into an equity partnership with a First Nation or that a province entered into a Heritage Agreement to ensure First Nation ownership and control over all Aboriginal remains and heritage objects found within the project area.

The Process of Developing the Wuskwatim Project Development Agreement

The six-year process leading to approval of the Wuskwatim Project Development Agreement involved intensive expert negotiations between NCN and Hydro along with comprehensive consultations with NCN Citizens.

NCN’s participation was coordinated through our own Future Development Office, which was in place until the project was ratified. It employed a team of community consultants who organized public consultation meetings for NCN Citizens as well as going from home to home to explain the deal and answer questions. NCN and Manitoba Hydro participated in ancient ceremonies at sacred sites near the Wuskwatim project as part of the overall negotiating process.

Initially we had to obtain the approval of our people to proceed with the negotiations to develop the project. An Agreement in Principle to explore the development of both the Wuskwatim and Notigi sites was ratified in 2001 by secret ballot vote. This then led to the development of a Summary of Understandings which outlined the basic commercial arrangements for the partnership in 2003 followed by a jointly developed and managed Environmental Assessment Process which concluded in 2004 and the construction of ATEC, a state of the art training facility in 2005. Each of these steps formed the basis for the final Project Development Agreement (PDA) to be concluded and ratified in 2006. A secret ballot vote on the Project Development Agreement was held on June 7 and 14, 2006 with 62 percent of NCN Citizens authorizing NCN Chief and Council to sign the Agreement. The signing ceremony was held June 26, 2006 and was attended by federal and provincial elected representatives and officials lead by Premier Gary Doer, MP Rod Bruinooge, Parliamentary Secretary for the Minister of Indian Affairs and Hydro CEO Bob Brennan.

The Agreement provided an equity partnership in the project of up to 33 percent if NCN elected to exercise that option. The project also offered considerable economic benefits to NCN through jobs, training and business opportunities during construction. Through its ownership position, NCN will receive long-term benefits through sustainable income to NCN from power sales.

To ensure that negative impacts from the project are avoided, rigorous monitoring plans were jointly developed and implemented during the construction and operation phases of the project to examine any long term impacts the project is having on the environment. In addition, to western science monitoring programs, NCN undertakes its own annual Ethinesewin (traditional knowledge) monitoring activities through its own monitoring company, Aski-otutoskeo. These activities provide valuable information about the impact of the project on the environment and any appropriate mitigation that is necessary.

Project Construction Complete after Five Years

Wuskwatim construction started August 6, 2006, with first power delivered 2,148 days later on June 22, 2012 when turbine generator unit 1 went on line, for a total project cost of $1.6 billion.

Through the nearly six years of construction, NCN realized significant benefits including over $143 million in direct-negotiated contracts with NCN businesses, training for more about 400 Citizens, and employment for over 370 individual NCN Citizens who represented about 630 hires on the project.

Since discussions began in 2006, the process delivered considerable capacity building for NCN Citizens involved in the process from negotiating skills with large utilities to employment skills on a complex resource development project that are transferrable to other projects. Additionally, NCN Citizens have new job opportunities at the Wuskwatim site now that it is operating and within the broader Manitoba Hydro corporation.

A Heritage Resources Agreement, the first of its kind in Canada, stated that anytime there is a disturbance in land a ceremony would be held. For NCN it also meant cross-cultural training would be provided to all workers and Ethinesewin (Traditional Knowledge) monitoring was equally recognized as part of the environmental and socio-economic monitoring for development projects like Wuskwatim.

PDA Renegotiation

A few years after the signing of the PDA changing economic circumstances primarily due to the global recession in 2008 and fracking, a new technology in the natural gas sector, threatened NCN’s investment and anticipated benefits from the project. In 2009, NCN and Manitoba Hydro agreed to a review of the PDA. A Supplementary Agreement was negotiated and agreed to in 2011 to address substantive reductions to the Partnership’s financial outlook.

However, the financial forecast continued to erode and the parties agreed to renegotiate certain terms of the PDA for a second time to ensure NCN would receive ongoing benefits from the project. These supplementary agreements ensured that the original intent and spirit of the 2006 PDA were more likely to be fully realized than if no changes had been made.

The second PDA supplement signed in 2015 also addressed excess water within the integrated hydro system, an issue that had become apparent after significant floods in 2011 and 2014 after the original PDA and PDA Supplement 1 were signed. Global pressures continue to impact the project, but NCN has received some significant benefits from the project since it went into operation in 2012, which has allowed it to begin addressing significant infrastructure and housing deficits in the community. A new Multi-Plex and Arbor are under construction and will be operational in the summer of 2018. Houses have been renovated and many new houses built. Roads in the community have been paved and new business investments have been made.

FUNDING FOR Community Programs

Signing the Wuskwatim Project Development Agreement in 2006 generated more than $5 million in compensation payments for adverse-affects from the project. NCN used that money to create the Taskinigahp Trust, which the Trust Office manages along with the various annual payments to the Trust in accordance with the PDA.

The Nisichawayasihk Trust and Trust Office, created in 1996 with the $40 million in compensation from the 1996 NFA Implementation Agreement, have a mandate to fund community programs that would otherwise not be possible through other sources.

Although the trust’s principle cannot be touched, investment income can be spent every year on community programs. The income from this Trust provided most of the funds for NCN’s investment in the Wuskwatim project as well as for NCN’s investment in other businesses, programs and services.

The Trust Office manages both Trusts and the CAP-CIP processes used to select projects for funding every year.

Other Economic Initiatives

Working to Build a Bright Future in Northern Manitoba

As economically beneficial as Wuskwatim is to NCN, the First Nation believes in diversifying its economy to create jobs and revenue streams from many sources for funding community programs, and providing services to our citizens that would not otherwise be available. NCN recognizes that it’s federal funding entitlements are not sufficient to meet the core needs of its citizens, let alone fund enhanced community development programs and services our Citizens seek that are often taken for granted elsewhere in Canadian society. Revenues from our economic development initiatives are used to support these programs.

NCN is constantly working to broaden its economic base and has many projects in development all of the time.

Treaty Land Entitlement Agreement

The 1997 Treaty Land Entitlement Agreement (TLE) partially fulfilled the land rights provided to NCN in Treaty 5, and it will add 324 square kilometres or about 80,000 acres to our Reserve Lands. NCN has an active and instrumental role in how this will finally be implemented, through the selection of new reserve lands. The land will be used for economic development, hydro projects, tourism, forestry and for protection of traditional sites for preserving natural medicines.

Mystery Lake Hotel

Before Wuskwatim, the Mystery Lake Hotel purchase (1998) was NCN’s largest revenue-generating investment. The long-established hotel has been a leading hospitality provider in Thompson since 1968 – renovated to add 38 more rooms in 2010 – NCN is ensuring it remains competitive in the community. It is an important business and employer in Thompson and it’s annual revenue is directed to the Petapun Trust, for use in community projects.

NCN Economic Development Corporation

The NCN Development Corporation was created in 1992 and is NCN’s major economic development vehicle for operating NCN businesses and corporations. In recent years, NCN launched the Thompson Family Foods Store (2012), NCN Three Rivers Store (2016), OCN Family Foods (2017), Aski’Otutoskeo Ltd., BCN High-Speed internet services and built a new OT Gas outlet to provide a modern gas bar and convenience store to serve the community. It successfully negotiated a Meetah Building Supplies franchise located in Onion Lake, Saskatchewan from which it derives ongoing revenues. Meetah was also a supplier to the Wuskwatim Construction Project.

Thompson Urban Reserve

NCN is also planning economic development opportunities on the Urban Reserve in Thompson. The reserve lands were officially added in May 2016, incorporating the Hotel and adjacent land. NCN envisions developing projects on the land to ensure economic growth and to serve both NCN and the Thompson market. The development will ideally enhance Thompson’s business community by providing facilities and services not yet available in the community. A gas bar is currently under construction as are renovations to the hotel. A new partnership has been formed with National Access Cannabis to operate a dispensary when cannabis is legalized.

ATEC – A Legacy for Tomorrow

NCN leaders acknowledge that an educated population is key to NCN’s future success. One legacy of the Wuskwatim project was construction of the $8.5 million Atoskiwin Training and Employment Centre of Excellence in Nelson House, the first such facility built on First Nation in Manitoba. Besides classrooms, it contains workshops for trades training, a library and Internet café, child-care centre, cafeteria and dormitories. The facility originally provided training for NCN Citizens and other northern aboriginals for jobs on Wuskwatim. Once Wuskwatim training was complete, it transitioned to providing post-secondary programs to meet community and northern-Manitoba education and training demands. Providing programs locally makes them much more accessible to NCN Citizens and avoids the expense and need to leave the community.

Treaty Land Entitlement Fulfilling the Promise of Treaty 5

NCN’s core reserve lands consist of 5,851.7 hectares as part of Indian Reserve 170, 170A, 170B and 170C. However, at the time the Crown was negotiating Treaties with First Nations in the 19th and early 20th centuries – including Treaty 5 made by NCN – reserve lands were to be allocated based on population size – 160 acres per family of five, adjusted up and down for larger and smaller families. That promise was never fulfilled, so in 1997 the Treaty Land Entitlement Framework Agreement was enacted to move the process forward. Over 79,000 acres are outstanding to NCN’s Treaty Land Entitlement and as of March 2011, almost 34,000 acres in 13 parcels have been transferred to NCN

reserve status.

Government by the People For the People

A Tradition of Participation and Consensus

Beginning in 1908 with the adhesion to Treaty 5 through to 1948, elections for NCN Chief and Councillors were typically held every year, except during World War II, when there was a five-year gap between 1939 and 1944. From 1944 to 1961 election timing varied, but from 1961 to 1998, they were generally held every two years in accordance with the Indian Act regulations.

Since the first election, 19 NCN Citizens have served as Chief. Jerry Primrose served the longest, being elected for five terms or 16 years, plus two two-year terms as councillor in 1978 and 1980. D’Arcy Linklater was the longest serving councillor totalling 20 years from 1994 to 2014, followed by William Moose serving 19 one-year terms between 1913 and 1931.

Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation’s Election Code was adopted in 1998, a major first step NCN took to restore its sovereignty, remove itself from the Indian Act and take control of our own election processes. It established that secret-ballot, democratic elections be held every four years to elect a Chief and six Councillors.

The Election code was modified in 2002, 2010 and again in 2013, to comply with certain Charter and human rights issues and to provide more administrative certainty and flexibility. Due process in the electoral process is ensured by the establishment of an Appeals Committee. Further historic steps were taken to assert sovereignty. After a number of years of consultation, 2017 was a year of further achievements. In August we approved our Aski-Pumenikewin (Land Code) followed by our Othasowewin (Constitution) in November. These historic laws incorporate our customary laws and ensure that we have modern forms of government, but incorporate our centuries old group discussion processes that form the basis for decisions to be made by our leaders.

Both documents provide law-making processes to strengthen our Nation. We will no longer have to seek approval from the Minister of Indian Affairs to manage our own lands and resources, our education system, or other issues of importance to our people. These steps by our Nation provide a strong foundation upon which to enter into negotiations with other levels of government to ensure our rights are recognized and protected in self-government agreements, which will be the next significant step in the journey of our Nation.

Our Vision is to Exercise Sovereignty that Sustains a Prosperous Future

Socially AND Economically

We are exploring many initiatives to ensure the future of our children.

Through our investment in the Wuskwatim Project, we are a partner in developing our water resources and at the same time ensuring the least possible impact on our land. We are also investing in other businesses that can bring us meaningful jobs and opportunities. We are connecting with the world via technology which will bring new business opportunities, while ensuring our original understanding of the Treaty is being honoured.

We have taken steps to establish a firm foundation for stable, effective governance which is essential to attract businesses, grow our local economy and increase our own source revenues. By taking these steps we have been able to begin significant rebuilding in our own community.

We know there is no single answer to our future, only an ongoing understanding that our treaties and relationship with the land must be protected and our relationships with the rest of the world must be based on honesty and mutual respect.